Blogs

St. Barbara – A Martyr, A Legend

‘Legend has it that…’

To “go down in history” is not an easy task. There are billions of people on this earth at this very moment and only a select few will be remembered 100, 500, 1000 years from now. Sure, records will be kept, and families will be able to construct their ancestry going back numerous generations. But to become a figure of history, a legend – someone who’s name is common knowledge and who’s deeds become household stories – is quite the accomplishment. So what does it take? Generally, it takes a mix of some history, a few facts, and a lot of good storytelling. One such story is that of Saint Barbara, patron saint of miners and artillery men.

The story of Saint Barbara and her martyrdom has been told in many ways by many different people, including the mining community of Kalgoorlie, Western Australia. In the middle of busy Hannan’s Street [well, country town busy], just a little ways down from the court house and its gold-tipped clock tower, sits Saint Barbara Square. It is a small break in the long line of shops and buildings and of course, it’s main feature is the St. Barbara fountain.

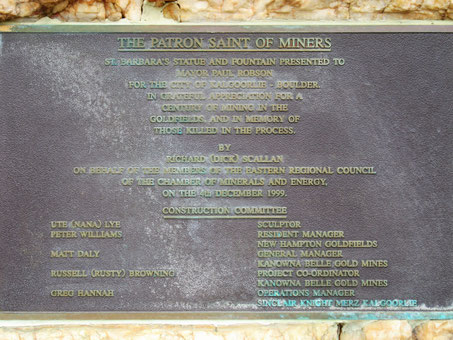

This monument was designed by Ute Lye and presented to the contemporary Kalgoorlie mayor, Paul Robson, on the 4th December 1999 by Richard Scallan and the Eastern Regional Council of The Chamber of Minerals and Energy (a very long title for a group that represents companies involved in collecting resources in Western Australia). The purpose of this monument was to celebrate 100 years of mining in the Goldfields and to commemorate the lives that had been lost to the mining industry. The names of those who worked on the monument are listed on a plaque affixed to the monument.

The statue in Saint Barbara Square is one of a young woman standing barefoot in a plain dress with a tie around her waist, holding a plain chalice-style cup. On either side of her stands two large quartz blocks, symbols of the mining industry. The monument sits in the middle of a fountain, with shoots of water spraying towards it from the edges of the oval-shaped base. Surrounding the statue, around the edge of the fountain, are a number of small plaques that tell St. Barbara’s story:

“Legend has it that…

St. Barbara was the Christian daughter of a heathen noble man who had promised her hand in marriage to a non-Christian suitor. She fled to hide in Mines underground. The Miners protected her and in return she passed on her Christian teachings. For two years she remained underground until shepherds informed her father of her whereabouts. Getting water, she was captured, sentenced to death and beheaded by her father.”

[I guess this is why she’s not the patron saint of shepherds.]

This is just one version of the story of Saint Barbara. The shared themes across most accounts are that she was a Christian daughter of a non-Christian noble, was promised to a man whom she did not want to marry and was executed by her own father. But many accounts tell of her faith being revealed when she requested a third window to be added to her father’s plans for a bath house. This third window would be a reference to, and symbol of, the Holy Trinity [Father, Son and Holy Spirit]. And instead of fleeing, it is often told that she was captured and either tortured in an effort to turn her from this faith or given the choice to live as a pagan or die as a Christian. Obviously she chose the latter, granting her the status of “saint” by the Catholic church. After executing his daughter, the pagan father (Dioscorus) was struck down by lightening on his way home, an act of retribution from God. And so St. Barbara become the saint to call on during a storm and was taken up as a patron to those who work with explosions [i.e. miners and artillery persons].

The lack of credibility in the historical accounts of Saint Barbara’s life and death led the Catholic church to pull her from the General Roman Calendar in 1969. [The General Roman Calendar is a liturgical calendar with all the days of the saints listed on it.] Though she is said to have died on 4 December [notice the date the statue was dedicated] sometime around 200-300 AD, the story of her martyrdom does not appear in Christian writings until the 7th Century AD, a good 300 or so years later. On top of this, her popularity and acclaim as a saint and martyr did not take hold until the 9th Century. But this affinity for the saint has since lived on in the lives of miners particularly. And though the authenticity of her story are greatly challenged, she continues to be remembered as a venerated saint and legend.

Bibliography

Johann Peter Kirsch, “St. Barbara,” The Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907 http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02284d.htm.

“Saint Barbara,” Monument Australia, 2010-2018, <http://monumentaustralia.org.au/themes/technology/industry/display/60644-saint-barbara/photo/1>.

“Saint Barbara,” NewWorld Encyclopedia, 2015, <http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Saint_Barbara>.

“Saint Barbara, Christian Martyr,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 2018, <https://www.britannica.com/biography/Saint-Barbara>.

Blucifer - Denver's Demon Horse

Earlier this year I had the wonderful opportunity to travel across the world to the USA to attend the wedding of a dear friend in Denver, Colorado. Roughly fifteen hours on a plane got me all the way from Sydney to LA. After a 4 hour wait, a missed flight, and a 4 or 5 hour flight to Denver via Sacramento (shout out to Southwest Airlines who sorted everything out for me with no fuss and no extra cost!), I landed in Denver, only a couple of hours late. I met up with my friend and together we made our way out of the airport. It was there in her car that I first heard of Blucifer.

I was told of a large blue statue of a mustang with glowing red eyes that stands outside of Denver International Airport. I chuckled at their description of a demonic-looking horse, but as we left the airport, that description became very real. This 32ft tall sculpture (that’s almost 10 metres for the rest of the world) depicts a fierce mustang, rearing up in an intimidating stance. The cobalt blue that covers the horse and the dark veins along the underbelly and face give a wild, stormy feel to this character. And of course, the red eyes do glow. Not just in a “painted bright red” way that I had anticipated but in a “red neon lights for eyes” way. There is no doubt that this horse exudes a fierce, wild power.

As it turns out, it’s not just the look of this horse that caused the locals to endow it with the nickname “Blucifer”. The horse was created by sculptor Luis Jiménez – a well-known artist of Mexican descent – and is a larger version of his “Mesteno” sculpture (“mesteno” is Spanish for “mustang”) that resides at the University of Oklahoma. Both versions are made from fibreglass and express a wild fierceness meant to symbolise the Southwest. It was this larger creation, though, that caused the death of its creator. On 13th June, 2006, as Luis Jiménez was in his studio, a large part of the sculpture fell on him, pinning him to the ground and severing an artery in his leg, ultimately causing his death. The work was completed by his sons and, in 2008, was installed in front of Denver’s relatively new international airport. And so this horse, with its fierce nature, glowing red eyes and the stigma of causing the death of its creator, was given the name “Blucifer”.

The horse is not the only point of controversy surrounding Denver International Airport however. The airport itself is said to have a number of questionable features, drawing in different conspiracy theories about its true purpose. The entire project began in 1980 with an investigation of six proposed sites on which to build a new airport that would replace the already existing airport. This alone sparked people’s interests as the question of why a new airport was necessary as the original one was functioning just fine closer to the city. In 1989 the location was decided upon and construction began in the hopes of opening the new airport in 1993. However delays pushed back the opening multiple times and didn’t take over as Denver’s sole airport until February 1995. Not only was this project well overdue, but it was also well over budget – 2 billion dollars over to be exact. More suspicions were raised as to the exorbitant cost of the airport. Add to that a fierce, red-eyed horse at the front and a myriad of strange murals and paintings inside and you have yourself an excellent candidate for conspiracy theories.

One such theory is that the airport was built by a Nazi group called the “New World Order”. The stone dedication marker credits the “New World Airport Commission” for contributing to the building of the airport, fueling various theories about what such a committee could be for. A simple Google search for such a commission leaves you with a list of conspiracies surrounding the airport, but a bit of digging shows that the New World Airport Commission was created simply to organise the opening of the airport and has nothing to do with anything other than the opening day. It has also been remarked that the airstrips for the airport, when viewed from above (as they generally are), create the shape of a swastika (the symbol of the Nazi party). However, it takes a bit of creative imagination in order to see a swastika rather than a pinwheel or a fan and may reveal more about the viewer than the airport.

Another popular theory is that the Freemasons had the airport built and use it as a base of global operations. This again stems from the dedication marker and apparently mysterious New World Airport Commission, as well as the Mason’s symbol that is carved into the dedication stone. The Freemasons, a fraternal organisation of individuals who trace their ancestry back to the local fraternities of stonemasons who regulated stone masonry in the fourteenth century, do have legitimate ties to the airport’s construction and dedication, but they are not involved with the day-to-day functioning or ongoing decision making of the airport.

Finally, the series of tunnels beneath the airport have sparked a multitude of theories about apocalyptic bunkers for elites, social groups such as Nazis or Freemasons, or even aliens residing below. The failed attempt to create an automated baggage system underground and the day-to-day workings of the airport have created many tunnels below. However, none of them lead to secret bunkers, and all of the plumbing and electrical wiring end at the lowest level of the airport.

The attitude of Denver International Airport towards these conspiracies hasn’t exactly helped to crush them however. Instead of expending the effort it would take to disprove every conspiracy theory that comes up, management seems to have decided to role with the theories a bit, taking in the free publicity, and even manages to have some fun with the theories. Workers have apparently been known to wear lizard masks in the underground tunnels while media groups tour the tunnel systems and the museum has featured an exhibition of some of the conspiracies in October of 2016.

Needless to say, the conspiracies of Denver International Airport and the interesting art that accompanies it have sparked much intrigue and publicity since its construction, and the horse is the most vivid of all of these. A giant blue mustang with blood-red eyes is bound to turn heads at the very least and certainly leaves an interesting first impression for anyone travelling to Denver.

Photographs provided courtesy of Denver International Airport.

http://images.flydenver.com/browse

Bibliography

“Blue Mustang – Denver, Colorado,” Atlas Obscura, <http://www.atlasobscura.com/places/blue-mustang>

John Wenzel, “The Definitive Guide to Denver International Airport’s Biggest Conspiracy Theories,” The Denver Post, 2016, <http://www.denverpost.com/2016/10/31/definitive-guide-to-denver-international-airport-conspiracy-theories/>

Sophie-Claire Hoeller, "People Have All Sorts of Crazy Conspiracies about Denver's Airport - Here's Why", Business Insider Australia, 2015, <https://www.businessinsider.com.au/denver-airport-conspiracy-theories-2015-10>

Athena - Goddess of war and wisdom

'She of the steel-grey eyes,

Wearing the dreaded aegis, shield which is ageless, immortal.'

- Homer, “Iliad” 2.446-445

Goddess of strategy, invention and the state. Daughter of Zeus and one of the twelve who rule from Olympus. One of the six females to sit among the twelve, yet considered to be the least feminine of the goddesses. One of the few deities to remain a virgin, holding no interest in marriage or romance.

Like most of the other Greek deities, Athena’s stories have been remembered and passed on for centuries and her image continues to be sculpted, painted and represented in a variety of ways, even in Australia. Standing outside of what used to be the first Savings Bank in Australia is a statue of this goddess, hand outstretched, towering over the mortals who walk past her. She stands in a regal, yet welcoming manner, wearing a Greek helmet and a sash across her chest, decorated by a monstrous face and snakes.

This figure is a copy of the 4th century BC bronze statue, probably carved by the Greek sculptor Kephisodotos, known for his statue of Eirene – peace – in the form of a woman holding a child. The original statue of Athena was discovered in Piraeus, Greece in 1959. It is either an original creation or, more likely, a representation of Hellenistic art. Her helmet has two owls on either side, displaying the goddess’s patron animal. Her sash with the snakes and gorgon head is reminiscent of Athena’s shield, Aegis, which holds the severed head of Medusa, killed by Perseus.

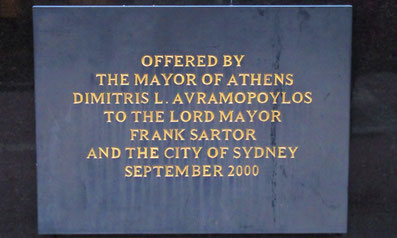

The statue, as told by the plaque below, was gifted to the city of Sydney and Mayor Frank Sartor by the Mayor of Athens, Dimitris L. Avramopoylos. The gift was presented in September of 2000 to celebrate the Sydney Olympics. It stands in front of what is now the Athenian Restaurant on Barrack Street in Sydney CBD. This elegant building, originally a bank, stands as an example of the 19th century, pre-nationalist era, with its imported building material exemplifying its high esteem.

The stories about Athena a vast and varied, but here are a couple to peak your interest. The story of her birth is one of the more unconventional births of Greek mythology, and that’s saying a lot. In an attempt to stop anyone cleverer than Zeus from usurping his throne, Zeus married “cleverness” herself, an Oceanid called Metis. When Zeus found out that his wife’s second child would be the one to overthrow him, he swallowed Metis while pregnant with Athena. This act caused Metis – “cleverness” – to become part of himself. Sometime later, Zeus began suffering from a

severe headache. Depending on the version of the myth you read, either Prometheus or Hephaestus struck Zeus in the head with an axe – cause that’s the scientific way to fix a headache – and out from the gaping wound rose Athena, fully grown and clad in armour, screaming out a war cry. And so Athena was “born”, and the second child destined to overthrow Zeus never came into existence.

Athena thus became known for being the most masculine of female deities. She never concerned herself with affairs of the heart and is perhaps the only Greek goddess to be considered a leader. Though a virgin, Athena did have a child in a typical Greek-myth loop-hole way. The story goes that Hephaestus, god of fire and blacksmithing, lusted after Athena, but to no avail. Eventually, in a desperate attempt to have her, Hephaestus lunged for her. Some part of him – sweat, tears or semen, depending on what version you read – ended up on her thigh. Disgusted, Athena wiped it off with a cloth and threw it to the ground. From this cloth, which held the essence of both gods, sprang a child who Athena took, raised and named Erichthonius. He later became a king of Athens.

Finally, perhaps the most well-known myth of Athena is the one about Arachne. Arachne was a mortal who boasted about her weaving skill, claiming to be equal to Athena herself. This, by the way, is never a good thing for Greek mortals to do. Hearing of these boasts, Athena descended from her throne in Olympus and, in disguise as an old woman (a favourite among Greek goddesses), confronted the girl about her rash claims. Arachne hurled insults at the old woman and challenged Athena herself to a competition. Revealing her divine self, Athena accepted. Both competitors created flawless works. In a rage at this outcome, Athena slashed up Arachne’s face. Instead of living with this visual mark of shame, the mortal girl hanged herself. Seeing the suspended body, Athena took a small amount of pity upon her and turned her into a spider, sprinkling her with poison and allowing her to continue weaving, but at the same time condemning her to hang in order to feel safe.

And so these stories live on. Through centuries of change, as nations rise and fall and cultures shift and alter, Ancient Greek thought and imagery continues to be present in our daily lives, across the globe. The image and memory of one who used to be considered a deity now stands in the narrow passage of Barrack Street, in the CBD of Sydney, thousands of kilometres away from where she was once worshiped.

Bibliography

Peter Miller, “The Athenian Restaurant (Former Savings Bank of NSW),” Flickr, 2012, <https://www.flickr.com/photos/64210496@N02/7170641328>

“Statue of Athene,” The Online Database of Ancient Art, 1995, <http://ancientrome.ru/art/artworken/img.htm?id=1652>

A Day with the Dead – a blog about Saint John’s Cemetery

On a gorgeous, sunny spring day, I walked through Saint John’s Cemetery in Parramatta. After taking the two trains it take me to get to Parramatta, I walked then walked through the maze of shops in Westfield shopping centre, desperately hoping I could remember enough of the last trip to not get too lost. Thankfully I could, and I found my way out the other side and conveniently close to the gates of the cemetery. The sun is beaming down and I have my sunglasses on and my jacket off. I lift the latch holding the large timbre gates closed and enter the cemetery.

Stepping through the gate, I stand under the small covering that welcomes visitors to the cemetery. To the side is a billboard of information about various aspects of the cemetery; some of its history, a map of the grave stones and a list of “some graves of interest”, including those of the first fleeters buried there.

Turning from the billboard and out to the cemetery, the first thing I

notice is the two large trees standing on either side of a "walkway" through the middle of the cemetery. Each tree is surrounded by graves, all scattered over the grounds. As I walk through the

cemetery, I feel as though I am in a completely different space. A brick wall surrounds the grounds, cutting me off from the rest of Parramatta. But the wall is only so high and the towering

buildings, both commercial and residential, on each side and the raised train tracks on yet another are clearly seen and heard. Yet the space of the cemetery stands completely still. There is no

one else around and there are few animals aside from the occasional bird or fly that invade the space. Everything around me stands deathly still.

Saint John’s Cemetery is Australia’s oldest surviving European cemetery. It was created in the 1790s when a servant of Governor Phillip, Henry Dodd, died supposedly from a chill and was buried on a hill not far from his home. This site then became Saint John’s Cemetery. His burial was the first public funeral to take place in Australia and many significant people in Australia’s history would follow him[1]. Yet, despite this obvious importance of the cemetery to Australian history, for decades the site has been neglected and left to slowly fall to ruins.

Vandalism”. “Disgraceful Condition”. “Apple of Discord”. “Neglected Dead”. “Vaults in Ruins”. “A City’s Disgrace”. These are just some of the phrases used over the decades in news headings to talk about Saint John’s Cemetery in Parramatta. From as early as 1868, newspapers were calling attention to threats on the cemetery, with accusations ranging from vandalism to neglect. For over a century, the call to take action, to remember their heritage and to look after the final resting place of some of Australia’s earliest European settlers has been spoken among Parramatta locals. For this cemetery ‘is an immensely significant site…due to its links to the history of the British Empire and world convict history’.[2]

I began looking into the history of Saint John’s Cemetery in the media after receiving a news clipping from a fellow historical student (who now has her own unique, historical blog at https://lonelybeaches.wordpress.com/) titled “Save cemetery for the nation”. Written in August of 1970, this article depicts a pretty sad and beaten picture of the cemetery’s condition. ‘Whisky and rum bottles…lay in a tomb which had been attacked by vandals’ and ‘tangled weeds and blackberries hide some of the graves’. The article speaks of an appeal made by Bishop H. G. Begbie, the Bishop in Parramatta, to restore the cemetery. This appeal was supported by the cemetery Trust as well as members of the Parramatta Trust. The hope was for descendants of the people buried in Saint John’s cemetery to take action in the restoration and to add weight towards an appeal to the Federal and State governments, as well as to the Parramatta City Council, for annual grants for maintenance.

As suggested above, this call was not a new endeavour. The earliest mention of the state of the cemetery presented on the Saint John’s Cemetery website (http://stjohnscemetery.jimdo.com/media/) speaks of vandalism that had hit a number of churchyards, including Saint John’s Cemetery. This news clipping from 1868 spoke of youths plucking ‘flowers planted by bereaved relatives and friends’ and warned that ‘the perpetrators of such wanton outrages were liable by law to severe punishment’[3]. The aim of this notice was to caution these youths of the consequences of such acts and hoped it would be enough to deter any subsequent vandalism. As the decades passed, Saint John’s Cemetery was described as being ‘in disgraceful condition’ and ‘so unsatisfactory as to give rise to much regret’, as well as being, ‘to a large degree, in all stages of neglect and decay’.[4] Comments such as these continued to be issues worthy of news space up until 2015 (see Clarissa Bye’s article “Historic St John’s Cemetery at Parramatta in state of neglect”).

The site has finally taken a turn in recent months, however, as the Friends of Saint John’s Cemetery work alongside Parramatta locals to restore and preserve what is left of this history. Recent events have worked to spark new interest in the cemetery, especially among the local community. Lots of work has been and continues to be done. And it is paying off; the cemetery is now quite pleasant to visit and all the graves can be easily accessed. Restoration is not enough however, and the need for funding and the proper telling of its history continues to be a prominent issue. The Saint John’s Project is working to give voice to the numerous stories of those buried in the cemetery. New medians such as Facebook, Twitter etc., are used to call for helping hands and funding, but the call remains the same as what was displayed in newspapers all those years ago: “save the cemetery”.

What draws me to the issue of keeping some old cemetery tidy and presentable is the bigger issue that Australia has with its neglected history. A few years ago, I took a trip around Europe. I visited fourteen cities and towns in nine different countries and was overwhelmed by the amount of history that stood, plain as day, in every street. Everything from old buildings to tucked away museums to cobblestone roads, Europe’s vast and rich history is out in the open for anyone to see. While thousands of people travel to Europe every year to see its historical sites, few people realise how much Australia has to offer in this very department. There are more “plain as day” sites in Australia than even I realised until very recently.

Much of this is simply because Australia, and especially its government, is not taking advantage of its historical resources. Sites like Saint John’s Cemetery would easily be popular tourist sites in a place like Europe, yet here in Australia, its often left unknown to tourist and Australians alike. It is a living testament to some of Australia’s earliest European history and can be quite a sight to behold on a sunny spring day. Walking distance from Parramatta’s historic Female Factory (yet another neglected historical site) and the Old Government House, the cemetery ‘is one of the jewels in Parramatta’s heritage crown’ and sits in a rich, historical area.[5] With the right resources, such as access to walking tours, good historical maps, clear signage and descriptions, etc., this area could achieve a very similar experience to walking through some of the old towns in Europe. The call to “save the cemetery” is not just a call for local Parramattans, but should be a call to Australians everywhere to save the history of this nation.

Notes:

[1] “Save cemetery for the nation”, Advertiser, 13 August 1970.

[2] “About – St. John’s Cemetery Parramatta”, viewed 28 October 2016, http://stjohnscemetery.jimdo.com/about-1/.

[3] "Parramatta. From Our Correspondent. Vandalism," Sydney Morning Herald (NSW: 1842 - 1954), Friday 4 September 1868, p.2

[4] Old Chum, "Old Sydney, Parramatta Revisited: Jesse Hack. St. John's Cemetery in a Disgraceful Condition. The Resting Place of Early Australian Pioneers. Alt's Tomb. The Kendall and Michael Families," Truth (Brisbane, Qld. : 1900 - 1954), Sunday 3 April 1910, p.11.

"St. John's Cemetery: Another Apple of Discord," Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, (Parramatta NSW: 1888-1950), Wednesday 14 October 1914, p.2.

William Freame, "Among the Tombs: St. John's Cemetery," Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, (Parramatta NSW: 1888-1950), p.4.

[5] “About – St. John’s Cemetery Parramatta”, viewed 28 October 2016, http://stjohnscemetery.jimdo.com/about-1/.

Bibliography

“About – St. John’s Cemetery Parramatta”. Viewed 28 October 2016. http://stjohnscemetery.jimdo.com/about-1/.

Freame, William. "Among the Tombs: St. John's Cemetery". Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate. (Parramatta NSW: 1888-1950) p.4.

Old Chum. "Old Sydney, Parramatta Revisited: Jesse Hack. St. John's Cemetery in a Disgraceful Condition. The Resting Place of Early Australian Pioneers. Alt's Tomb. The Kendall and Michael Families" .Truth (Brisbane, Qld. : 1900 - 1954) Sunday 3 April 1910. p.11.

"Parramatta. From Our Correspondent. Vandalism". Sydney Morning Herald (NSW: 1842 - 1954) Friday 4 September 1868. p.2

“Save cemetery for the nation”. Advertiser. 13 August 1970.

"St. John's Cemetery: Another Apple of Discord.Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate. (Parramatta NSW: 1888-1950) Wednesday 14 October 1914. p.2.

"Il Porcellino" - the lucky pig

‘For

be she shallow, be she deep,

No woman can a secret keep;

Which all should think upon who see

The monument which here will be.'

- From The Bronze Boar of the Mercato Nuovo, in Legends of Florence

It’s a cold, wet day in the city of Sydney. I make my way from where the bus stopped on Elizabeth Street, through Martin place and up to Macquarie Street. And there, sitting across the road, is Il Porcellino, an Italian boar that sits, quite regally, in front of Sydney Hospital. I walk pass this boar about once a week and have seen plenty of tourist groups crowding around the boar, but have never stopped myself to see why it sits there. Not until I started writing this blog. As I approach the statue, I find out something quite surprising; the sculpture is actually a fountain. At the base of the boar’s front hooves is small pool of water, decorated with frogs, tortoises and other creatures, and at the bottom of this pool is slot for coins to drop. In the many times I had walked passed this sculpture, I had never got close enough to notice the pool of water.

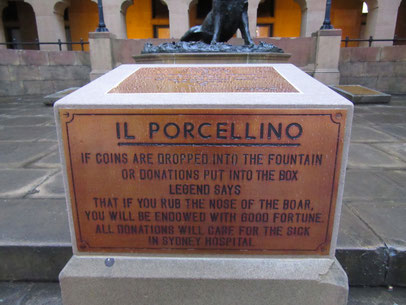

Il Porcellino, meaning “the little pig”, is one of many replicas of a bronze boar that stood in the straw market of Florence in 1634. The one that now stands in front of Sydney Hospital is a popular site for tourists and is apparently the most photographed object in Macquarie Street. The plaque that sits on the front of the sculpture claims that if you rub the boar’s nose as you drop a coin into the fountain, ‘you will be endowed with good fortune’. Also, as a bonus, the money you drop into the fountain is donated to the Sydney Hospital, Australia’s oldest, permanent hospital.

The original sculpture was made in 1634 by the bronze master Pietro Tacca. The boar was originally made for a fountain in Italy’s Boboli Gardens, but ended up on a fountain in the “Mercato Nuovo”, which literally means “new market” and was originally a place to sell luxury items. Like the fountain that sits outside Sydney Hospital, this boar had a place for visitors to drop coins between the boar’s jaws for good luck. As time went on, the tradition of rubbing the boar’s nose as they did so formed, which resulted in a shiny golden snout. Replicas of this statue can be found around the world, from Sydney, Australia to Florence, Italy to Arkansas, USA.

The boar was most likely inspired by a Hellenistic age marble boar. This boar was probably a representation of the Calydonian

Boar, a creature from Greek mythology. Sent by Artemis, the Greek goddess of the hunt, to devastate Calydon when its king failed to honour her with the proper rituals, the Calydonian Boar was

eventually hunted down and killed by the Calydonian hunt. Among this group of hunters was a female huntress, Atalanta, who was the first to wound the monster and therefore won its

hide.

There is another legend about the origins of the bronze boar that is told in Leland’s “Legends of Florence”. It is said that the boar was once the son of a rich lord who had married a barren wife. Because she could not give him a child, the lord abused his wife, calling her a useless creature and telling her that if she could not bear him a child, she had no reason to stay. The wife spent her days weeping and praying for an heir, but she remained barren.

One day, while out in the fields, the wife saw a drove of pigs go by with their little pigs. The wife, with a jealous bitterness filling her heart, cried,

'So the very pigs have offspring and I none. I would as I were as they are, and could do as they do, and bring forth as they bring forth, and so escape all this suffering!'

Unbeknownst to her, a witch-spirit dwelt among these very pigs and took her at her word. Soon afterwards, the lord’s wife became pregnant. The lord was greatly pleased and anticipated the birth of a son with joy. However, when the lady gave birth, it was not a human child that was born, but a pig! Yet both parents were simply glad to have offspring of any kind and treated the boar as a great pet. The boar learned to talk, and as he grew older began to chase after girls.

One girl in particular struck his fancy. A beautiful but poor girl. The young boar asked this girl’s parents for her hand in marriage but was met with laughter and refusal. However, the young girl could see that this boar was not a common or lazy pig and, being daring enough to do anything to become richer, agreed to the marriage.

On the bridal night, just as the sun set, the young girl found to her great pleasure that the boar she had just married turned into a fine young man. Their union had allowed the boar to shed his beastly nature at night, though he returned to his previous state as a boar once the sun rose. However, if the girl should speak of this to anyone, the young man would once again turn into a boar for life, and the girl would be turned into a frog.

Inevitably, the poor girl could not keep this secret for long, and instead confided in her mother, who then imparted the secret onto her friends, and them onto their friends. The truth spread fast and far and by the end of the day the whole town knew of the secret. The poor girl was turned into a frog and the young man was once again a boar for life. And now, when the boar goes down to the spring each day to drink, he cries,

'Lady Frog! lo, I am here!

He to whom thou once wert dear.

We are in this sad condition,

Not by avarice or ambition,

Nor by evil or by wrong,

But ’cause thou could’st not hold thy tongue;

For be she shallow, be she deep,

No woman can a secret keep;

Which all should think upon who see

The monument which here will be.'

The Florentine statue stands in the market-place as a reminder of the boy and his wife who said too much and warns of the dangers of telling secrets.

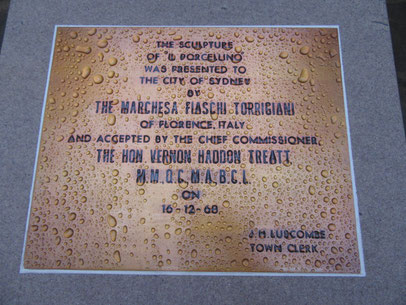

The sculpture that stands outside the Sydney Hospital was presented on the 16th of December, 1968 to the city of Sydney by the Marcheasa (an Italian noblewoman) Clarissa Torrigiani. It stands as a symbol of the friendship between Italy and Australia. It is also a memorial to the Marcheas’s father and brother (Thomas and Piero Fiaschi), both honorary surgeons who worked at the hospital.

Sydney Hospital was Australia’s first permanent hospital and began construction in 1811. It was started by Governor Lachlan Macquarie who proposed the building of a general hospital to replace the tent hospital that had been set up in 1788 on what is now George Street in The Rocks. The hospital was nicknamed the “rum hospital”, as the three contractors who funded the building of the hospital were granted a limited monopoly on the distribution of spirits in return for their funding.

So the next time you are in Sydney and walking down Macquarie Street, make a stop at the statue of the noble boar to drop a coin into the fountain and give that famous nose a rub. Then let your lucky day begin!

Bibliography

Judith Godden, Hospitals, Dictionary of Sydney, 2008, http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/hospitals, viewed 25 August 2016.

Laila Ellmoos, Sydney Hospital and Eye Hospital, Dictionary of Sydney, 2008, http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/sydney_hospital_and_eye_hospital, viewed 25 August 2016.

Leland, Charles, Legends of Florence Collected from the People, First Series, “ 2010, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/32786/32786-h/32786-h.htm, viewed 5 September 2016.

Shirley Fitzgerald, Il Porcellino, Dictionary of Sydney, 2008, http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/il_porcellino, viewed 25 August 2016.

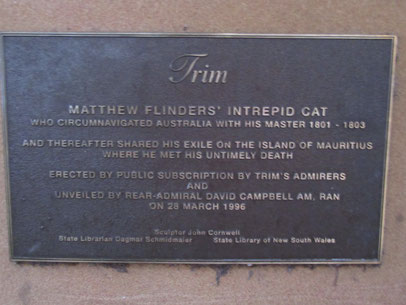

Trim: the cat who circumnavigated Australia.

‘Trim,

the best and most illustrious of his Race, –

the most affectionate of friends, –

faithful of servants,

and best of creatures.’

-Matthew Flinders, in his biographical tribute to his cat Trim-

Standing outside the NSW State Library is a very stately statue of Captain Matthew Flinders, a name any Australian high schooler will recognise as an important figure in the European settlement of Australia. Flinders was an accomplished navigator and chart-maker in the Royal Navy. Sailing on the HMS Investigator from 1801 to 1803, it was Flinders who first circumnavigated mainland Australia.

In December of 1803, Flinders sought help on an island off the east coast of Madagascar after the schooner he was sailing back to England began letting in too much water. It was here, on the island of Mauritius, that Flinders lost his ‘good-natured purring animal’ friend, Trim the cat.

From birth, Trim captured Flinders’ interest and respect. In his biographical tribute to his cat, Flinders speaks of ‘the signs of superior intelligence which marked [Trim’s] infancy’. From that moment on, a deep friendship formed between pet and master and Flinders watched with a proud interest as Trim grew and learned from the seaman that surround him over the various voyages they partook together.

Trim did indeed seem to be a very intelligent and adaptive creature. According to Flinders, he learned not only to not fear the water, but also to swim. He learned to climb ropes and steps alike with great speed and agility. He even came to do tricks with his fellow seaman. However, his one fault, as Flinders confessed, was his vanity. Trim would sit in the middle of the seaman’s walkway and spread out his two white paws, making anyone who wished to walk past him stop to admire them.

Flinders noted that the cat seemed to ‘take a fancy to nautical astronomy’. Trim would sit with the time-keeper (an instrument used to measure longitude) and interact with the young man who was tasked with marking down the time. The one item that seemed to attract his attention more was ‘a musket ball slung with a piece of twine, and made to whirl round upon the deck’ with one’s finger.

Trim, it seems, was beloved by all crew members. At dinner time, he would be the first to the table. Once everyone was seated, Trim would ‘put in his request’ for dinner and continue his modest mew until fed. If his petition was refused, Trim would whip a person’s mouthful off their own fork ‘with such dexterity and an air so graceful, that it rather excited admiration than anger’. Trim would then finish off his morsel and move on to the next diner to repeat the process.

Flinders traveled with Trim on a number of voyages and with him, this one cat traveled the globe. In fact, Trim seemed to be more comfortable out at sea than at “home” in England. Trim did not suit the manner of English living and apparently could wreak havoc on a good set of china dishes if a mouse so happened to dash past.

One August night, on their way back to England in 1803, after circumnavigating Australia, the ship Trim was on was shipwrecked. By some feat of daring or by simple dumb luck (or perhaps it took a bit of both), Trim survived that night and made it to Wreck Reef, off the coast of Queensland. There, he and the surviving crew salvaged food and water for three months, until Flinders found and rescued them.

Having rescued his shipmates, Flinders set off again for England, with Trim by his side. However, it soon became apparent that the schooner they were on would not reach their destination. Flinders, therefore, was obliged to stop on the island of Mauritius for assistance, an island that was then controlled by the French. During this time, war between England and France had broken out (again) and Flinders, his crew and Trim, feared by the French General De Caen to be spies, were taken prisoner on the island. Trim was clearly a comfort to Flinders and his men during their captivity and a hint of jealousy can be detected in Flinders’ account of the cat’s nightly adventures without him.

When the men were moved to Maison Despeaux, Trim was handed over to the custody of a French lady and her young daughter. However, after only a fortnight, it was announced that Trim was nowhere to be found, despite the offer of a monetary reward for his return. Flinders was quite heartbroken to hear that ‘poor Trim was effectually lost’ and feared that the loyal cat had been eaten by a poor, hungry slave.

Flinders ends his account with a moving epitaph, commemorating the life and noble attributes of his dear friend, and lamenting his untimely death. The full epitaph, along with Flinders’ own account of his memories of Trim, can be read in his biographical tribute to Trim, written in 1809.

‘Peace be to his shade, and

Honour to his memory’.

Bibliography

Matthew Flinders’ biographical tribute to his cat Trim, December 1809, The Flinders papers, <http://flinders.rmg.co.uk/DisplayDocumentb322.html?ID=92&CurrentPage=1&CurrentXMLPage=1>.

H. M. Cooper, 'Flinders, Matthew (1774–1814)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, <http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/flinders-matthew-2050/text2541, published first in hardcopy 1966, accessed online 26 August 2016>.

You can do it, too! Sign up for free now at https://www.jimdo.com