‘For

be she shallow, be she deep,

No woman can a secret keep;

Which all should think upon who see

The monument which here will be.'

- From The Bronze Boar of the Mercato Nuovo, in Legends of Florence

It’s a cold, wet day in the city of Sydney. I make my way from where the bus stopped on Elizabeth Street, through Martin place and up to Macquarie Street. And there, sitting across the road, is Il Porcellino, an Italian boar that sits, quite regally, in front of Sydney Hospital. I walk pass this boar about once a week and have seen plenty of tourist groups crowding around the boar, but have never stopped myself to see why it sits there. Not until I started writing this blog. As I approach the statue, I find out something quite surprising; the sculpture is actually a fountain. At the base of the boar’s front hooves is small pool of water, decorated with frogs, tortoises and other creatures, and at the bottom of this pool is slot for coins to drop. In the many times I had walked passed this sculpture, I had never got close enough to notice the pool of water.

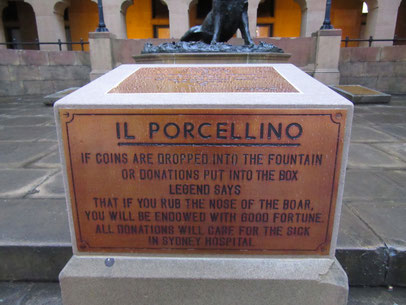

Il Porcellino, meaning “the little pig”, is one of many replicas of a bronze boar that stood in the straw market of Florence in 1634. The one that now stands in front of Sydney Hospital is a popular site for tourists and is apparently the most photographed object in Macquarie Street. The plaque that sits on the front of the sculpture claims that if you rub the boar’s nose as you drop a coin into the fountain, ‘you will be endowed with good fortune’. Also, as a bonus, the money you drop into the fountain is donated to the Sydney Hospital, Australia’s oldest, permanent hospital.

The original sculpture was made in 1634 by the bronze master Pietro Tacca. The boar was originally made for a fountain in Italy’s Boboli Gardens, but ended up on a fountain in the “Mercato Nuovo”, which literally means “new market” and was originally a place to sell luxury items. Like the fountain that sits outside Sydney Hospital, this boar had a place for visitors to drop coins between the boar’s jaws for good luck. As time went on, the tradition of rubbing the boar’s nose as they did so formed, which resulted in a shiny golden snout. Replicas of this statue can be found around the world, from Sydney, Australia to Florence, Italy to Arkansas, USA.

The boar was most likely inspired by a Hellenistic age marble boar. This boar was probably a representation of the Calydonian

Boar, a creature from Greek mythology. Sent by Artemis, the Greek goddess of the hunt, to devastate Calydon when its king failed to honour her with the proper rituals, the Calydonian Boar was

eventually hunted down and killed by the Calydonian hunt. Among this group of hunters was a female huntress, Atalanta, who was the first to wound the monster and therefore won its

hide.

There is another legend about the origins of the bronze boar that is told in Leland’s “Legends of Florence”. It is said that the boar was once the son of a rich lord who had married a barren wife. Because she could not give him a child, the lord abused his wife, calling her a useless creature and telling her that if she could not bear him a child, she had no reason to stay. The wife spent her days weeping and praying for an heir, but she remained barren.

One day, while out in the fields, the wife saw a drove of pigs go by with their little pigs. The wife, with a jealous bitterness filling her heart, cried,

'So the very pigs have offspring and I none. I would as I were as they are, and could do as they do, and bring forth as they bring forth, and so escape all this suffering!'

Unbeknownst to her, a witch-spirit dwelt among these very pigs and took her at her word. Soon afterwards, the lord’s wife became pregnant. The lord was greatly pleased and anticipated the birth of a son with joy. However, when the lady gave birth, it was not a human child that was born, but a pig! Yet both parents were simply glad to have offspring of any kind and treated the boar as a great pet. The boar learned to talk, and as he grew older began to chase after girls.

One girl in particular struck his fancy. A beautiful but poor girl. The young boar asked this girl’s parents for her hand in marriage but was met with laughter and refusal. However, the young girl could see that this boar was not a common or lazy pig and, being daring enough to do anything to become richer, agreed to the marriage.

On the bridal night, just as the sun set, the young girl found to her great pleasure that the boar she had just married turned into a fine young man. Their union had allowed the boar to shed his beastly nature at night, though he returned to his previous state as a boar once the sun rose. However, if the girl should speak of this to anyone, the young man would once again turn into a boar for life, and the girl would be turned into a frog.

Inevitably, the poor girl could not keep this secret for long, and instead confided in her mother, who then imparted the secret onto her friends, and them onto their friends. The truth spread fast and far and by the end of the day the whole town knew of the secret. The poor girl was turned into a frog and the young man was once again a boar for life. And now, when the boar goes down to the spring each day to drink, he cries,

'Lady Frog! lo, I am here!

He to whom thou once wert dear.

We are in this sad condition,

Not by avarice or ambition,

Nor by evil or by wrong,

But ’cause thou could’st not hold thy tongue;

For be she shallow, be she deep,

No woman can a secret keep;

Which all should think upon who see

The monument which here will be.'

The Florentine statue stands in the market-place as a reminder of the boy and his wife who said too much and warns of the dangers of telling secrets.

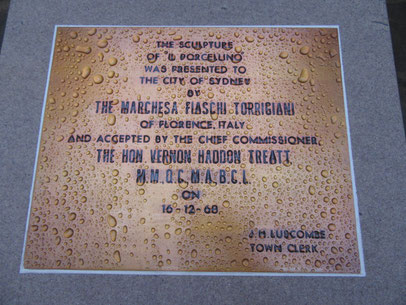

The sculpture that stands outside the Sydney Hospital was presented on the 16th of December, 1968 to the city of Sydney by the Marcheasa (an Italian noblewoman) Clarissa Torrigiani. It stands as a symbol of the friendship between Italy and Australia. It is also a memorial to the Marcheas’s father and brother (Thomas and Piero Fiaschi), both honorary surgeons who worked at the hospital.

Sydney Hospital was Australia’s first permanent hospital and began construction in 1811. It was started by Governor Lachlan Macquarie who proposed the building of a general hospital to replace the tent hospital that had been set up in 1788 on what is now George Street in The Rocks. The hospital was nicknamed the “rum hospital”, as the three contractors who funded the building of the hospital were granted a limited monopoly on the distribution of spirits in return for their funding.

So the next time you are in Sydney and walking down Macquarie Street, make a stop at the statue of the noble boar to drop a coin into the fountain and give that famous nose a rub. Then let your lucky day begin!

Bibliography

Judith Godden, Hospitals, Dictionary of Sydney, 2008, http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/hospitals, viewed 25 August 2016.

Laila Ellmoos, Sydney Hospital and Eye Hospital, Dictionary of Sydney, 2008, http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/sydney_hospital_and_eye_hospital, viewed 25 August 2016.

Leland, Charles, Legends of Florence Collected from the People, First Series, “ 2010, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/32786/32786-h/32786-h.htm, viewed 5 September 2016.

Shirley Fitzgerald, Il Porcellino, Dictionary of Sydney, 2008, http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/il_porcellino, viewed 25 August 2016.

Write a comment